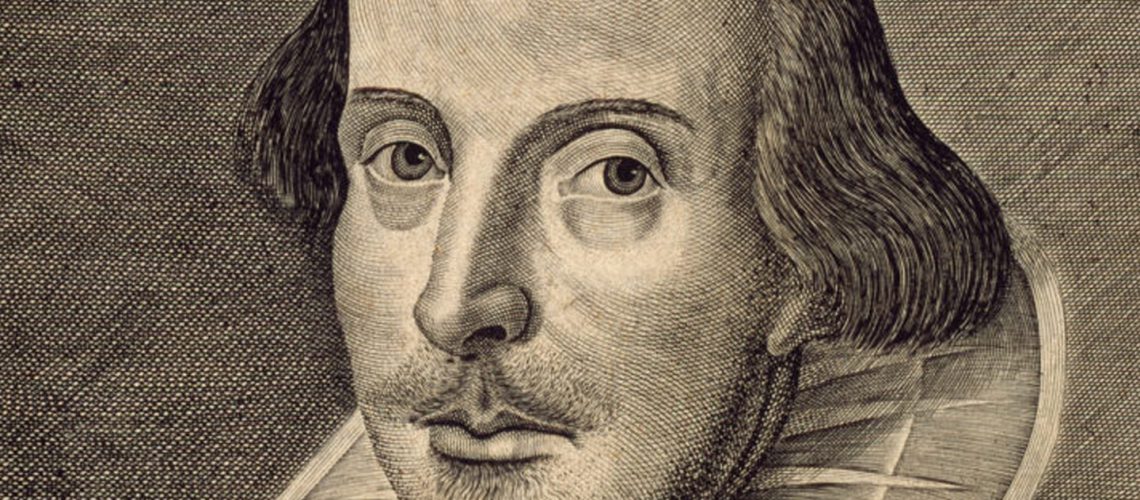

Last week, to celebrate the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth, I focused on the “eternal Shakespeare”, arguing that Shakespeare is timeless and therefore, and paradoxically, that he is also timely. Here are a few of the timeless truths in Shakespeare that are also and always timely.

In Romeo and Juliet the difference between true and false love, i.e. rational and irrational love, is highlighted. This is evident in Romeo’s blasphemous exclamation that “heaven is here / Where Juliet lives”. Juliet is Romeo’s alpha and omega, his beginning and his end. She is the goddess to which he owes the sum of all his worship. It is for this reason that he chooses this “heaven” even when it becomes his hell. In Dante’s Inferno the lustful are described as “those who make reason slave to appetite” or as those who let their erotic passions “master reason and good sense”. Like Paolo and Francesca in the Inferno, Shakespeare’s lovers have overthrown reason in pursuit of passion. Embracing their madness and blindness, their “love” has surrendered to the force of feeling. Their love is headless and therefore heedless of the bad consequences of the bad choices being made. Shakespeare and Dante are well aware of the danger of separating love from reason. Love, like faith, must be subject to reason; a love that denies or defies reason is illicit and is not really love at all.

In some ways, Romeo and Juliet can be seen as a cautionary commentary on the two great commandments of Christ that we love the Lord our God and that we love our neighbor. The two lovers deny the love of God in their deification of each other, with disastrous consequences, and their respective families deny the love of neighbor in their vengeful feuding. It could be said that the venereal and vengeful passions of Verona represent the culture of death in microcosm. A society that turns its back on Christ and His commandments is on the path to suicide, to nihilistic self annihilation. If the lessons are not learned and the warnings heeded, the sinful society will be doomed to be damned.

Similar lessons to those taught in Romeo and Juliet are taught in The Merchant of Venice in which the test of the caskets shows that true love is about dying to oneself so that one can give oneself fully and self-sacrificially to the beloved. This true love is contrasted with the self-centred desire of those who fail the test. In similar vein, the test of the rings at the end of the play reinforces the necessity of self-sacrifice in the sacrament of marriage. Finally, of course, Portia’s timeless wisdom reminds us that we must love our neighbor, showing the quality of mercy that God has shown to us.

In Julius Caesar, Shakespeare pours scorn on Caesar’s vanity, on Antony’s bloodthirsty opportunism, on Cassius’ ambition, and on Brutus’ brutal idealism. Yet he is not cursing from the perspective of a worldly cynicism but from that of a believing Christian at a time when believing Christians were being tortured and put to death by the vanity of monarchs, by bloodthirsty opportunists, by political ambition, and by brutal idealism.

There is, however, a deeper level of meaning in Julius Caesar that is all too often overlooked completely. It is the sound of silence within the play; the scream in the vacuum of the play’s vacuity. It is the unheard and unheeded voice of the virtuous. It is the voice of Calpurnia, which, if heeded, would have saved Caesar’s life; it is the voice of Portia, which, if heeded, might have urged Brutus to think twice about his involvement with the conspirators. It is the voice of the Soothsayer and of the augurers. It is the voice of Artemidorus, a teacher of rhetoric, whose note to Caesar is devoid of all rhetorical devices and direct to the point of bluntness. The note is not read, the voices are not heard, and the consequences are fatal. All that was missing in the play is the one thing necessary, the still, small voice of virtue and wisdom that the proud refuse to hear.

The whole of Hamlet turns on the crucial distinction between reason and will, and between that which is and that which seems to be, and the test of success is the extent to which the protagonists conform their will to reason and to the reality to which it points, irrespective of all appearances to the contrary. This is Hamlet’s struggle throughout the play. In the end, through conforming his will to reason and in connecting reason to faith, he becomes the willing minister of Divine Providence, bringing justice to the wicked King Claudius and restoring justice to the realm.

In many ways, Macbeth can be seen as the anti-Hamlet. Whereas Hamlet begins in the Slough of Despond, temperamentally tempted to despair, he grows in virtue throughout the play until he reaches the ripeness of Christian conversion and the readiness to accept his own death as part of God’s benign Providence. Hamlet grows in faith because he grows in reason; Macbeth loses his faith because he loses his reason.

In a more general sense, the dynamism of the underlying dialectic in Shakespeare’s plays, and therefore of the dialogue, is centred on the tension between Christian conscience and self-serving, cynical secularism. Whereas the heroes and heroines of Shakespearean drama are informed by an orthodox Christian understanding of virtue, the villains are normally moral relativists and Machiavellian practitioners of secular real-politik.

In the final analysis, the right reason for learning Shakespeare is to learn the right reason that Shakespeare teaches!